Imagine the alarm goes off.

It’s 2:00 AM. A containment alarm is screaming. Steam is venting across the walkway. Your heart rate spikes to 140 beats per minute. Your hands are shaking.

In this moment, your “Business Continuity Plan” (BCP) might as well be written in Sanskrit.

If your recovery procedure is a 40-page PDF with 12-point font and long, passive-voice paragraphs, it will not be read.

We often design safety procedures for auditors sitting in air-conditioned offices. We should be designing them for terrified operators standing in the rain.

Here is the neuroscience of why traditional ISO 22301 documents fail in real crises, and how to design for the “Adrenaline Brain.”

The Neuroscience: Cognitive Tunneling

When a human enters a “Fight or Flight” state (triggered by Core Drive 8: Loss & Avoidance and Core Drive 6: Scarcity), the brain fundamentally changes how it processes information.

- The Prefrontal Cortex Shuts Down: This is the part of the brain responsible for logic, complex reading, and nuance.

- Cognitive Tunneling Sets In: Peripheral vision disappears. You can only focus on what is directly in front of you.

- Fine Motor Skills Degrade: You become clumsy. Scrolling through a PDF on a tablet becomes difficult.

In this state, a sentence like “Ensure that the tertiary valve isolation protocol is enacted within 15 minutes” is unintelligible. The brain cannot parse the syntax.

The Audit Trap: Completeness vs. Usability

Auditors love detail. They want the procedure to cover every liability.

- Auditor’s Goal: “Is it comprehensive?”

- Operator’s Goal: “How do I stop the leak?”

These two goals are often mutually exclusive. A document that satisfies the legal team usually paralyzes the response team.

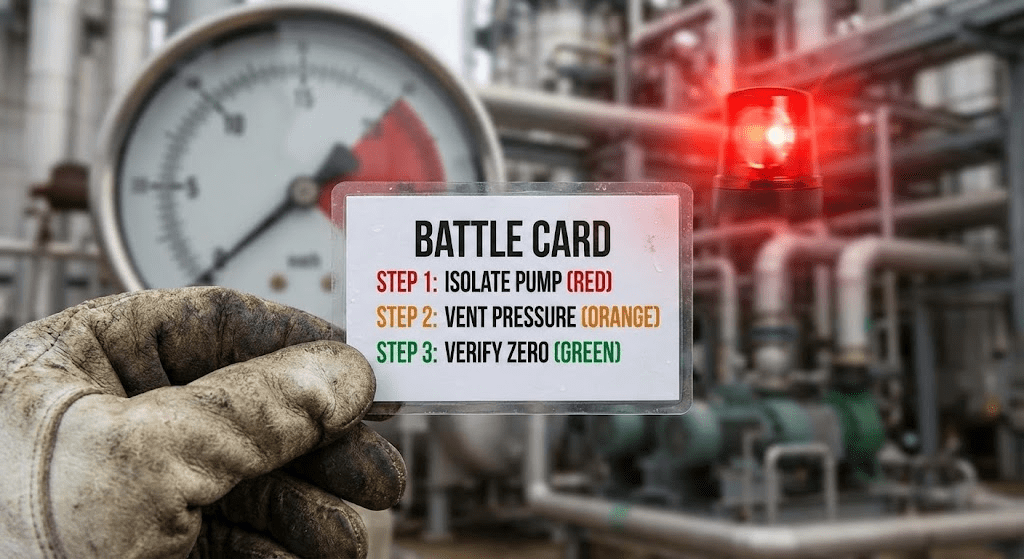

The Solution: “Battle Cards”

To fix this, we need to borrow from aviation and the military. We need to stop writing “Manuals” and start designing “Battle Cards” (or Action Cards).

Here are the three rules for designing for the Adrenaline Brain.

1. Verb-Noun Syntax (The “Caveman” Rule)

Strip away all politeness and grammar. Use imperative commands.

- Bad: “The operator should proceed to the lower deck and ensure the isolation of the main intake.” (Too much processing required).

- Good: CLOSE Main Intake Valve. GO to Lower Deck.

Your procedure should sound like a drill sergeant, not a lawyer.

2. The “Rule of 5” Chunking

Cognitive science tells us that working memory is limited, especially under stress.

Do not present a list of 20 steps.

Break the procedure into “Chunks” of 5 steps maximum.

- Phase 1: Containment (5 Steps)

- Phase 2: Notification (3 Steps)

- Phase 3: Recovery (5 Steps)

This allows the brain to “close the loop” on small tasks, providing a dopamine hit (Core Drive 2: Accomplishment) that counteracts the panic of the adrenaline.

3. Visuals Over Text

In a high-stress environment, a picture is not worth a thousand words; it is worth a thousand seconds.

Don’t write: “Locate the red lever behind the secondary pump.”

Show a photo of the lever with a bright yellow arrow pointing to it.

Use Visual Anchors—color-coding, icons, and bold text—to guide the eye through the tunnel vision.

Conclusion: The “Stranger Test”

Resilience is not about having the most words; it is about having the fastest understanding.

Test your BCP today with the “Stranger Test.”

Hand your recovery procedure to someone from a different department (a Stranger). Put a stopwatch on them. Ask them to simulate the shutdown.

If they have to stop and read a paragraph, your plan failed.

If they can look, act, and move in under 10 seconds, you have successfully designed for the Adrenaline Brain.

Next Step:

Take your most critical Emergency Procedure. Cut 50% of the words. Increase the font size by 50%. Add a picture. Laminate it.

Now you have a plan.

The information in this article was partially generated by Google’s Gemini, an AI language model, and has been reviewed/edited for accuracy and relevance.

Leave a comment